13 February 1981

The morning news reported a ship sunk during

the night off Norfolk. This was somewhat unusual, but off Norfolk

can mean a large area or even the closest reporting organization.

By the end of the day the reports were becoming more specific

on the location and relation to the severe storm that had lashed

the Maryland and Virginia coast on Thursday. Soon there were

sparse reports of the Norfolk and Chincoteague Virginia Cost

Guard rescue attempts. However there still was no report of survivors;

the ship had vanished on its run from Norfolk to New York.

We had been scuba diving the East Coast

from New Jersey to North Carolina for nine years, mostly on World

War II shipwrecks. The mid-Atlantic Ocean has mostly sandy bottom

with very few reefs thereby leaving only shipwrecks for scuba

diving. Ship wrecks newer than the war were few and I had not

heard of one within diving depth since I started diving in the

1960’s. The most recent had been the Marjory McAlester,

an ocean tug lost off Cape Lookout in 1969 and the Ethyl-C off

Cape Henry the same year.

Several months had passed when I met the

husband of a friend; a Navy Seal stationed in Norfolk. Later

that night the subject of diving came up and he started to tell

us the story of his Seal team efforts to rescue the crew of the

Marine Electric. The whole story took an hour and although he

had not been part of the team, many of his friends had. It was

a brave attempt in weather so severe that passage and anchoring

were risky, much less diving into the wreck in heavy seas. Until

that time I was not even aware of the exact location of the disaster,

much less the fact that it only lay in 130 feet of water just

off Chincoteague, one of out favorite diving areas.

With early May came the good weather and

the start of dive season. Also came word that two of our charter

captains knew of the location of the Marine Electric, although

it was a longer boat ride that usual. First we tried from Chincoteague,

but the boat developed engine problems half way out and the Captain

returned inshore not wishing for a total breakdown that far off-shore.

As June of 1981 approached, our Ocean City charter captain told

us he knew the location and wanted to go there on the next charter.

He ran a large (60 foot) crew boat and it would be the perfect

dive boat for that trip. By this time, there were many stories

of the Marine Electric including the investigations into the

cause of the sinking and some salvage attempts for the large

Bronze propeller. Also by that time we knew it was broken in

two and the short section was the stern where the bridge and

crew quarters were located. The insurance divers reported the

bow section upside down and the stern lying on her side.

Finally one Saturday in early June we headed

to the SS Marine Electric. We were not the first to go there

by then and stories came with details of no visibility, cold

water and lots of coal dust. In general, it was not a nice dive

and not one for a novice. The Marine Electric had been carrying

6,000 tons of fine coal slurry (pea size and smaller) which now

enveloped the wreck already lying in a silty bottom area. By

now the water was starting to warm up, at least on the surface,

but the bottom would still be in the low 40’s. The captain

anchored his boat; "The Good Time Diver" in the area

that he thought would be the stern. We geared up in out wet suits,

scuba tanks for the 130 foot descent and having no idea what

to expect - expect bad to no visibility. On dives like that even

the brightest dive lights are of little help. Today the cold

water stayed bright all the way down and by the time my wife

Penny and I reached the wreckage we still had more than 15 feet

of visibility.

Usually as I explore an old steel wreck

I have visions of the explosions and fire that sunk so many during

the war. Then came depth charging by the navy looking for German

U-Boats, followed by navigational clearing with explosives and

wire drags. After the war many were salvaged for copper and brass

and many were blown in one way or another. So I was used to seeing

twisted wreckage, sometimes unrecognizable. The hurricanes do

more than their share when they send ground swells all the way

to the bottom and over the years most ship wrecks experience

recurring damage. I was never able to sort out the cause of the

damage. In this case the wreck was new. No one had blown it up

and there had been no major storms or Hurricanes. I expected

to see an intact ship.

We were anchored near the stack where it

met the deck area and the scene met my expectations. However

I soon noticed that the bridge area was in shambles. Most windows

were broken with thick glass pieces hanging in the frames. There

was twisted and confusing wreckage all around. The bridge was

half full of sand with only part of the large radar protruding.

The sand level was just at the middle of the bridge. Even the

helm was not recognizable. Then I remembered the large stack

with the big black diamond and white "M" was also half-buried

and parallel to the sand. The entire stern had sunk exactly half

way into the sand with the deck vertical to the bottom.

I swam through a door near the bridge that

was also horizontal; every thing recognizable was horizontal

from the norm. The first room appeared to be a galley as it had

several tables attached to the floor, which I perceived as a

wall. I cautiously entered a hall worrying about the loose wires

and other strange clutter. I looked into a room and saw furniture

with light streaming through a single closed porthole. I investigated

some more looking in another room. It too had a porthole, but

sand was packed against it. I later realized I must have been

at least 15 or 20 feet below the level of the ocean bottom outside.

I returned to the hallway leading out worrying about loosing

my sense of direction without a safety line. With the welcome

light of outside I noticed an orange life ring on the ceiling.

I pulled on it. There was so must bouyency that at first I though

it must be attached to the wall. I started to leave and then

remembered that it must have the ships name on it. Few things

last very long containing the name. I pulled and stood it on

end looking at the back with my light. There it was clearly "Marine

Electric Wilmington Del". My wife and long time dive buddy

waited above the railing outside. I rolled the life ring to the

edge and let it fly toward the surface zooming past her face.

The crew on the boat said the ring leaped in the air upon surfacing

and laid next to out boat. They reached overboard and retrieved

it reading the name more clearly than I had in the darkness on

the bottom.

Although 130 feet is not very deep for

sport diving, it still is very limiting for safe duration and

ours was all too quickly reached. Penny and I returned to the

anchor line and ascended to 20 feet for the first of two decompression

stops before returning to the boat. The sun was warm and we soon

warmed up while comparing stories of what the ship looked like.

Everyone was a bit confused by the damage and twisted steel.

Several divers had investigated the area just forward of the

bridge windows and reported twisted metal for a few feet and

then no more wreck. The break had been just in front of the bridge

and must have accounted for the magnitude of the damage in that

area.

After more than two hours and a good lunch

we re-suited and made the second dive that is usually shorter

than the first due to the residual nitrogen acclimated in the

first dive. Calculating the length of the second dive is based

on surface time since the first. We had only fifteen minutes

on the second exploration. Once again we went in the bridge area

still having trouble understanding the jumble. Only the signal

flag box and the radar seemed to make any sense. Returning outside

I decided to explore the deck area rather than go inside, due

the shortness of the dive, which was almost over. Near the bridge

was a mast and lots of cable. Everything was twisted around something

and I was doing my best no to join the mess. I stopped to look

at my dive timer as the planned departure time was approaching

fast. I leaned against the mast and noticed a dark object wrapped

around it. Must be one of those signal flags, but why would there

be a signal flag flying from the mast? Despite my shortness of

time I untwisted the thick nylon from the steel cable which itself

was twisted around the mast. Penny was waving bye-bye as she

returned on time. I shown my light on the thick wrinkled material

illuminating a big white "M" - the same symbol I had

seen on the side of the stack. I was failing to understand how

it was attached to the cable and my time was overextended. I

cut the material as close as I could to the steel cable and stowed

the flag in my bag where it would safely ride out the return

trip to my first decompresson stop.

On the deck of the dive boat I saw Penny.

She was already out of her gear and waiting for me to return.

With some excitement, I said, "I have a flag". She

said, "don’t bother, John brought one of those signal

flags up and it is rotting cotton...throw it back". Well

I knew it was not a signal flag, nor made of cheap rotting cotton.

I pulled it out and held it up, "it’s the ships flag!".

Several years later a friend looked at it and commented: "What’s

so spectacular about that artifact is that is makes me realize

that ships still sink. It should be on display somewhere."

The ship's flag with the big white "M"

that was flying from the mast when the ship sunk in now on display

in the lobby of MEBA where many of the crew were trained.

Doug and Penny Buckley

November 1996

Cotton signal flag

Cotton signal flag

Nylon ship's slag flying from the mast

Nylon ship's slag flying from the mast

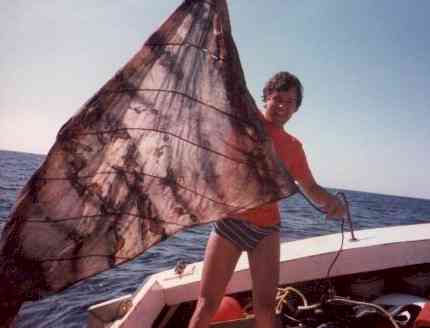

Lifering from galley area in stern

Lifering from galley area in stern

Back to the Library